Over the course of 2023, I was fortunate enough to traverse districts in Bunyoro, Lango and other areas in Northern Uganda. Most of the sites I visited are directly or loosely linked to Omukama Kabalega, one of the greatest rulers of the 19th Century.

Whether it’s the Emin Pasha monument at the Mparo Royal Tombs, Semei Kakungulu’s home and it’s war artifacts in Gangama, Fort Patiko in Gulu or the Mwanga and Kabalega capture monuments at Kangai in Dokolo, it is evident that what have come to be sites of historic and tourism value in these areas were influenced by Kabalega reign and and its turbulent lapse.

It’s a complicated web; from Emin Pasha ‘courting’ Kabalega over 30 days only to be given a big fat “NO”, Baker’s Nubian soldiers looting Kabalega’s palace and allegedly introducing homosexuality, to the eventual capture of the resilient Omukama alongside his friend and ally Kabaka Mwanga in some godforsaken swamp at Kangai in Dokolo.

Some of the major sites that interested me most were;

Mparo Burial Grounds

Mparo Grounds is the royal burial site for Omukama Kabalega and other members of the royal clan. Located along the Hoima-Masindi road at Mparo village approximately 4 km out of Hoima town, the site is one of the must-visits while on a tour of Hoima.

Inside the large grass-thatched cone-shaped mausoleum, Kabalega’s remains rest, wound in layers of bark-cloth. Bark-cloth is traditionally used for embalming among other purposes. The embalming effects of back-cloth can last up to 50 years.

Royal regalia belonging to Kabalega is also found in next to the levelled grave.

Emin Pasha Monument

A 12-stare monument painted white is erected a few meters outside the burial shelter where the gallant king rests. It’s one of the features that will surely capture your attention as soon as the cool breeze of Mparo enchants your soul into the histories.

The monument marks the spot where Kabalega met Emin Pasha on 22 September, 1877.

Emin Pasha had been sent from Egypt by then ruler of the Egyptian empire Khedive Ismael who had a vision of extending the borders of his country as far as Uganda and all countries south of Gondokoro.

Pasha, born Isaak Eduard Schnitzer, baptized Eduard Carl Oscar Theodor Schnitzer, met Kabalega to persuade him to look into the possibilities of annexing Bunyoro to the Egyptian administration under the Equatorial Province.

Bearing gifts from Egypt, the Equatoria province governor spent 30 days trying to lure Kabalega into accepting the deal. After the 30 days, Kabalega looked Pasha in the eye and tore his hopes into shreds with an irrevocable no.

According to Mr. Bwogo Rujumba, a tour guide for Bunyoro Kingdom who speaks about the old times with such unquestionable intellect and fact, Kabalega told Pasha that it would be a shame if he gave away his Kingdom over some gifts and unrealistic promises.

“Kabalega was strong willed and had an unwavering determination to stand by his decision and conviction. He couldn’t accept a deal in which he would lose his kingdom irrespective of the shiny objects Pasha dangled before his eyes for 30 straight days. He (Kabalega) was fluent in Arabic so he communicated efficiently with Pasha. The no was final,” Rujumba noted.

I met this eloquent, middle-aged man back in April 2023 during a tour of Western Uganda. I haven’t met any other tour guide that tells a gripping story that holds me spell-bound for 47 minutes.

READ: How Explore Uganda Campaigns are Bolstering Domestic Tourism

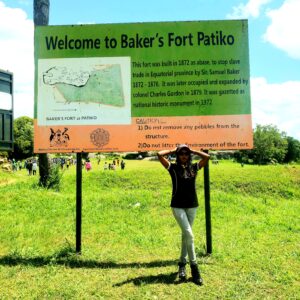

Fort Patiko/ Sir Samuel Baker’s Fort

After dodging an attack from Kabalega, Sir Samuel Baker fled up North, to a place called Patiko where he put up a fort.

But how exactly did a Governor-General of the Equatorial Province end up in a situation where he had to run for dear life?

Following the unanticipated response from Kabalega, Pasha, neither a good simp nor a shrewd negotiator, tucked tail back up North to report his fruitless visit.

“But he was a good man, an honest fellow. Upon his return to Egypt, Pasha described Kabalega as a friendly, talkative and flexible man. He didn’t go bitter despite his failed attempt at earning the Khedive a territorial extension thanks to Kabalega’s refusal,” Rujumba added.

Shortly after Pasha’s futile attempt, a mischievous envoy named Samuel Baker arrived in Bunyoro to engage Kabalega on the same. Unlike Pasha, a peace-loving fellow, Baker was a moving red flag of a purported ally who ‘offered to help’ Kabalega fight slave trade.

Kabalega’s encounter with an errant officer

Baker moved with a large number of Nubian soldiers “who were extremely indisciplined.”

“In the short time they were here, they wreaked havoc – making repeated demands for food and beer from the locals, harassed and raped our women and introduced homosexuality. Homosexuality is not a recent practice. It was introduced here in the 19th century by the soldiers of sir Samuel Baker. All these reports were reaching kabalega but he still tolerated Baker’s presence,” a visibly furious Rujumba further narrates.

After a few unyielding meetings with Kabalega, Baker left Kihande, where Kabalega’s palace was then and went to Masindi where he put up a camp for his soldiers at a place called Kijura.

After getting established in Masindi, Baker took the gloves off; started exchanging cheaply manufactured goods for ivory. Ivory trade was reserved for Kings, who bought it from locals.

“The fool had started interfering with Kabalega’s business. He also made repeated provocations by carrying out military maneuvers with his soldiers in front of Kabalega’s palace. Baker’s unruly soldiers made open insults against Kabalega.”

Taking his provocation a notch higher, Baker once hoisted an Egyptian flag at his camp, insinuating that the whole of Bunyoro belonged to Egypt. This irked Kabalega so much that he sounded his drum and summoned people into the palace, consulting about what he should do for the officer.

Kabalega forced into exile

It is said that Sir Samuel Baker ‘noticed’ that there was a meeting going on at Kabalega’s. He stormed the palace and burnt it down, forcing Kabalega into temporary exile to a place called Kibwoona.

While there, Kabalega organized his army to attack Baker and possibly capture him. By the time he reached the camp, however, Baker had already escaped.

This attempt at capturing Baker was nicknamed ‘Obulemu bwabarigota Isaansa’ meaning a fruitless attempt of capture.

Baker had run to a place called Patiko in Gulu – the now famous tourist attraction named Fort Patiko.

“From that time, the fool continued to ruin Kabalega, writing damningly, painting a bad picture of Kabalega. In his book titled “Ismailia”, Baker tarnished the reputation of the King and the Banyoro people as a whole. Whatever he wrote, when it was received in the UK, it was believed as true,” Rujumba notes.

He adds, “That’s why, when the British colonialists came here, they were hell-bent on putting out Kabalega. He made 3 requests for peace talks which were all rejected by Captain Frederick Lugard because of the perceived bad image painted by Baker. Baker is blamed for Bunyoro Kingdom’s conquest and disintegration.”

Rujumba emphasizes that Kabalega should never be perceived as a blood-thirsty war-monger because he fought a war which was forced on him.

“Pasha had no problem, Baker was the slithering snake. The only good thing about Baker is that he came and helped geographers to locate the source of the Nile. The whole fighting between the British and Kabalega was largely premeditated because they (British) believed the derogatory reports Baker wrote. As a great King that he was, Kabalega couldn’t go down without a fight,” he notes.

Kangai – where hell broke loose

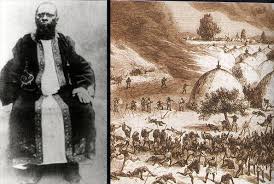

Back in the 1870s, a Langi Rwot named Owiny Akullu had honed his skills as a traditional warrior and created a strong army with which he conquered over 100 battles.

His fighting tactics and warrior spirit drew in the attention of an embattled Kabalega across the Nile. The latter asked Rwot Akullu for help which was granted. Akullu moved with part of his army to Bunyoro where he helped Kabalega win a couple of battles against the British.

The spear, bow and arrow effects, however, weren’t as damaging in the presence of guns and realizing the continued loss of their soldiers, Akullu advised Kabalega and his ally Kabaka Mwanga of Buganda, to retreat.

The three fled to Lango where they stayed for 5 years – regrouping, re-strategizing.

On April 9, 1899, while the two Kings rested in Kangai, British collaborators Semei Kakungulu and Andrew Luwandaga launched a well-planned attack, smoking Mwanga and Kabalega out.

Fleeing into a swamp, the the kings realized they had been surrounded and had no plausible escape route. Like the last kicks of a dying horse, the two kings, alongside their troops, put up an inconsequential fight before they were captured a few metres from each other.

Two monuments were erected at the spots of capture for remembrance.

The Kabalega trail, one would argue, is a forever piece of history that tourists can always enjoy, especially millennials like myself who barely sat through the Social Studies classes back in primary school.

I must admit that with the pieces of evidence scattered around Bunyoro and Lango, a history class on the same is not just bearable, it is something I would want to hear. I can recast the characters, reimagine the scenes because the storyline flows a bit more seamlessly now.